BERNHARD

SACHS

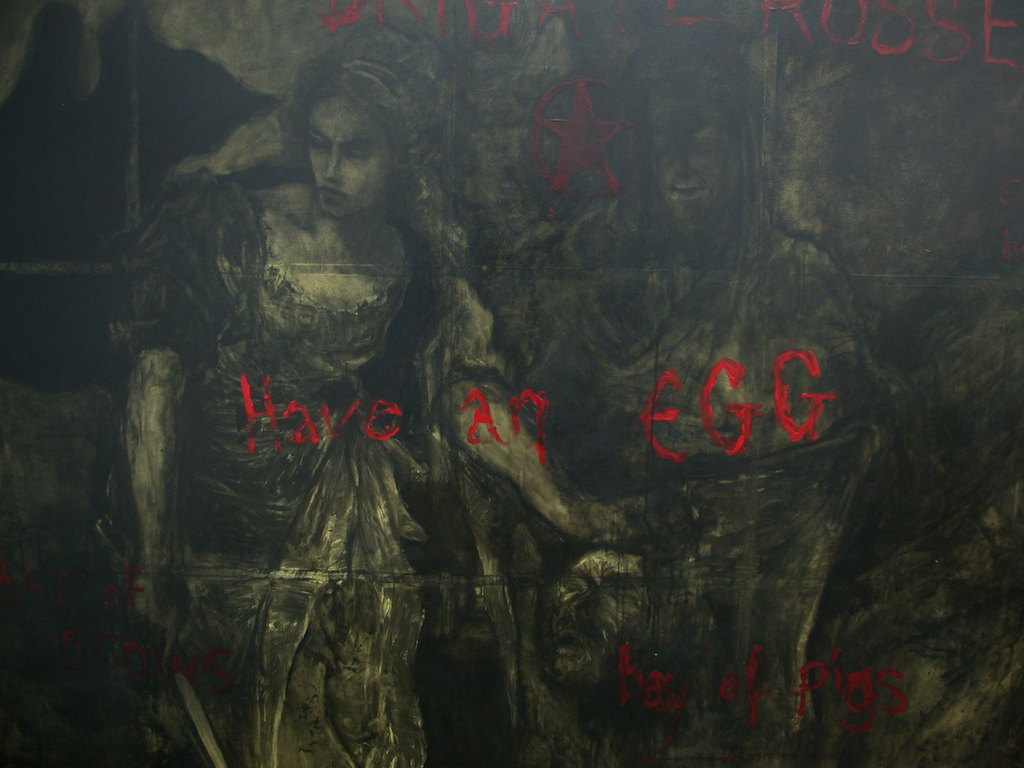

The art of Bernhard Sachs is overwhelming, the practice unceasing, urgent, compelling. He writes significant tracts in his artist’s statements for each exhibition dating back to the 1980s. He comes of age in an Australian art world hardly cognisant of its avant-garde or its art history. It’s a whiteness story in a land of black trauma. Everything is troubled, scared, denied. History itself is tormented – nothing is settled.

I spoke with artist Derek Kreckler recently. He collaborated with Bernhard in the late 1970s/early 1980s and he remembers Bernhard was always obsessed with salt, blood and death, and with the Death Camps under the Nazis in Germany during WW2. At art school, Bernhard became famous for nailing dead fish to trees and using rabbits in his actions and installations.

Sach’s practice is dedicated, unflinching. It is not interested in markets and commodities. His trade is in the

histories of ideas and ideologies, in the turmoil of world politics and the catastrophes humans wreck upon each

other in the name of nations and states, in the pursuit of power, money, and belief. Bernhard understood that the

making of history and the tragic noise of humankind, repeat endlessly because we just can’t think and feel at the

same time. We get seduced by power, by the surge of the crowd, by our desire.

Sachs was committed to an avant-garde that has already failed but nevertheless persists at the heart of practice,

in the experimentalism that drives it. Although the western artworld has been contorting itself for almost a

hundred years, trying to maintain an ethical and political practice in this field is beyond many. This is why

Sachs’ work is significant. He speaks to generations of practitioners trying to establish a voice for an art that

matters. An art that has purpose, an art that contributes to the critical ideas of its time. It’s not an easy art.

Practice is not easy in Sachs’ school of thinking. It’s a commitment to the socio-political world through its role

as witness. Practice is a way of life.

The physical and psychological activity demonstrated through the repetitive reworking of ideas and images to create an archive of over-drawing and re-dating to enable layers of physical history within one work is quite astonishing. Almost breathless in its performativity. Twirling the two-dimensional surface through ecstasy and obliteration until the work becomes extinct and is thrown into the void of its own living history. This is a wild approach. An attempt to archive the practice in the present. To bury and perhaps commemorate its passing.

So much of Bernhard’s work is autobiographical but he also stretches his experience and his history so that he

can accommodate a wider analysis of the past and failures of various ideological positions. Situating his own

blood in his work is a sly sabotage—an insistence that the wounded/diseased corporeal body needs recognition;

that everybody is the body of Christ. The stamp that he used to mark his work is modelled on the Vatican stamp.

Bernhard took his practice seriously. It was almost a religion.

Bernard’s contribution to the art world is astonishing for its intellectual depth. In many ways, he is a rouge philosopher, pushing his theoretical meanderings through dark installations which dive into the materiality of art – drawing and painting – and its comeuppance in photography, film and reproductive media. For him the photograph was an X-ray and he utilized this idea to demonstrate how history is made and revised; performed and compromised. Explorative X-rays of paintings by curators and conservationists fascinated him. His interest in the ontology and epistemology of history and of various art mediums became conceptual tools to explore through art. But as Janet McKenzie argues:

In spite of the literary critique that dominates most commentary on the work of Bernhard Sachs, and the artist’s own interest in theory, his drawn images are physically beautiful, dramatic and confrontational. Australian born, of German descent, the Germanic tradition of Marx, Nietzsche and Freud, inform his worldview. Like Anslem Kiefer, Sachs addresses the physical weight of European culture, particularly the inescapable weight of the German tradition since World War II.1

Bernhard’s ‘late work’, is analysed in his 2009 exegesis titled APOSTASIS: Latework and Allegory, where he clearly aligns himself with the Frankfurt School of critical theory. An influence that will dominate postmodernism as it repeats history, amidst the shattering of philosophical positions via deconstructive and post-structuralist theory. In this milieu Sachs inserts himself and his history. The son of a German refugee who escaped Germany after the devastation of World War II. The trauma of the father and his father before him, a man, who like many in Weimer Germany renounced his religion and Jewish heritage.10 Sachs enters this psycho-social miasma and sets to work as an artist to approach this history through poetic means. Apostasies is the renunciation of religion or belief. In medical terminology it refers to the termination of disease. It is tempting to see these ideas played out in the artist’s practice as a psychoanalytic therapy. The son attempting to heal the father’s history.

I am watching the video of Sachs’ 2009 exhibition Anathema/Anachronism/Apostasy at the Margaret Lawrence Gallery (VCA). The camera focusses on the crowd and pans to the musicians – the sax and guitarist in one space; then the singers; then Sachs and a woman playing a grand piano. It is a decadent, salon style avant-garde happening. None of the singers or musicians know how to play their instruments, they are improvising as best they can. It comes across as experimental music because that is what the audience expects.

Sachs is a master of irony. The artist describes the exhibition as ‘an allegorical theatre or opera of the world’ after Walter Benjamin’s 1924 text The Origin of German Tragic Drama. But he adds that: ‘The mise-en-scene is resolutely Faustian. Goethe’s Faust is the legacy, the shadow through the Benjamin text’ and it is Faust’s text on the music stands that the unrehearsed singers and musicians are instructed to sing and play as best they can, discarding page after page onto the floor of the gallery so that it becomes strewn with the ghosts of history.2

Surrounding this cacophony there are huge pictures of historical incidences, abominations (anathema). The mass suicide of over 900 people at Jonestown in Guyana in 1978 when a deranged guru-like character – Jim Jones – convinced people to die for belief (apostasy). Ashley Crawford writes:

Sachs’ resuscitated images are chilling indeed, as are the captions: ‘Arm-in-arm in death . . . some of the bodies of People’s Temple members, including a small child, after taking poison during the mass suicide pact’ and ‘BEFORE the throne of Jim Jones . . . the bodies of the faithful’. And . . . the plaque that featured in the Jonestown ‘chapel’: THOSE WO DO NOT REMEMBER THE PAST ARE CONDEMNED TO REPEAT IT.3

NOTES

1 Janet McKenzie, ‘Conceptual Drawing: Recent Work by Bernhard Sachs, Mike Parr, Greg Creek and Janenne Eaton’, Studio International, 28 October, 2010. https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/conceptual-drawing-recent-work-by-bernhard-sachs-mike-parr-greg-creek-and-janenne-eaton. Accessed 21 June 2023.

2 Bernhard Sachs, Apostasis: Latework and Allegory, 26.

3 Ashley Crawford, ‘Between Bacchanalia and Melancholia’, Photofile 31 (2009): 31. Crawford traces the source of this statement on history to the philosopher, George Santayana, who wrote in his 1905 treatise Life of Reason that: ‘Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it’.

© 2025 professor ANNE MARSH | SITE BY jamie charles schulz