Art Action

Case studies on Australian performance art with notes on the remediation of live art on screen

PUBLISHED IN

Anne Marsh in Richard Martel (ed), Art Action 98-18, Les Éditions Intervention, Le Lieu, Centre for Art Action, Quebec, 2025, pp. 412-435.

CATEGORY

Performance Art

YEAR

2025

Art Action

Case studies on Australian performance art with notes on the remediation of live art on screen

Since the 1990s, there has been a renewed interest in the body art of the 1970s and a return to embodied practice after the amnesia of the 1980s, when textual and linguistic art practices were prioritized, resulting in critiques of the gendered body as essentialist. Since 2000, a concurrent renewed interest in art activism has led performance artists to take up the challenge to produce interventionist art and political statements. In this paper, I want to present a series of case studies that prioritize visual and experiential analyses of the work as a way of bringing the work itself closer to the reader.

It is 1993: I want to attend a performance by the Australian performance artist Linda Sproul. I read in the press release that I need to book over the telephone. I ring up and get a recorded message. It is a song by The Beatles: Listen. Do you want to know a secret? Do you promise not to tell? Whoa oh… a. After I listen to a segment of the song, I register my intention to attend via voicemail. When I arrive at the venue, I am locked out, along with everyone else who has booked. People are annoyed.

Eventually, the doors of the big Edwardian house open. We are ushered through the grand hallway and into a small room at the back. Here, we encounter an installation. Everyone is crushed into the tiny space. It takes a while to adjust to what is there. In the bay window, there is a female shop dummy clad in a nineteenth-century corset. On the opposing wall, a shop display presents high-heeled shoes. Directly in front of me, above the ornate fireplace, is a video projection. It is difficult to comprehend at first. It is a fragment of the body: a woman’s neck is tightly cropped just below the chin above the breast. It is moving and contorting. I realize that she is screaming, but everything is silent. She cannot speak. Eventually we are all told to leave the space and are ushered into the hallway again, where we are told to arrange ourselves along the corridor. The hallway is between the door we have entered—now closed—and a grand staircase. Gradually, our attention is drawn to the stairs.

A woman appears on the top landing. She is dressed in a suburban nightgown and she strikes a pose as though she were praying. Then she takes the nightgown off. It falls to the floor. She turns around to reveal her back, which looks red, but it is difficult to see. Now naked, she descends the staircase slowly and at the bottom, on our level, she puts on a pair of the high-heeled shoes from the installation we saw previously. She picks up a rubber-clad torch and some cards and then parades down the corridor created by the audience. She stops now and then and bends over, offering people the rubber torch and encouraging them to shine the light on her back. At first we think she is painted, but then we realize she has been beaten. It is clear that her beating was done by a professional dominatrix—the welts on her back are precise and incised, and she has been whipped, caned, scratched: there is a precision to the wounding. She hands out small cards: on one side, a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz of a small child, above which the words ‘teeth, nails, knife, belt, cane, whip’. On the reverse the phrase ‘love my memory’.

When she reaches the end of the corridor of people, she puts on a cocktail dress, opens the entrance doors, turns to the audience and thanks them for coming. She walks back along the line of spectators shaking hands, apologizing for the fact that there were not enough chairs. The dramatic change of mood is disruptive and unsettling as she denies her body and her wounds.

Provocative, alarming and highly problematic in terms of any ‘correct’ political line, the performance remains, in my memory, a resounding statement about the plight of women experiencing domestic violence. But that is only one side of the story. The other issue for Sproul at the time was the then-current fashion of sado-masochism. Sproul argued that the difference between the vogue for s/m fashion, s/m clubs and the real pain of physical abuse was linked to privilege and choice. According to Sproul, “If you come from a safe place of power, of course it is incredibly thrilling to hand that power away. If you don’t come from a safe place, how much is thrilling and how much is enactment?” Sproul went to The House of Domination in inner Melbourne to get her beating for the performance and was told by the mistress that she had a much higher pain threshold than her regular clients. In an interview, Sproul pointed out that this was because her body had learnt to tolerate pain.1 Adult survivors of childhood abuse continue to heal from scars hidden from public view and frequently struggle with anxiety, depression or anger. Victims of abuse also bear the burden of secrecy in a society that is uncomfortable with acknowledging the reality and prevalence of abuse.

Fiona McGregor and AñA Wojak collaborated as a performance art duo under the name of senVoodoo from 1999 until 2008. Initially they performed at parties and cabarets in Sydney’s club scene and then moved into theatre and gallery-based performance work. In 2005, as part of the Residency Program at Performance Space in Sydney, senVoodoo conceived Arterial as a three-channel video. In 2006, they developed the work as a live performance that toured throughout Poland (Wojak’s homeland). In 2008, the work was performed live at the Experimental Art Foundation in Adelaide, where the video installation was also shown.

Arterial presents two women shrouded in white, their faces and bodies covered in a translucent material. They walk slowly towards one another with their arms extended. It is a Butoh-like walk — each step is almost imperceptible, a measured shuffle. The soundtrack is ethereal, comprised of the sounds of the inside of the body: blood pulse, breath and heartbeat.2 They walk on a long white scroll of photographic paper and both have cannulas in the veins of their wrists. As their blood spills, it splashes onto the photographic emulsion where it binds and congeals, allowing the scroll to be exhibited as a residue of the ritual.3 McGregor says that the performance is about loss and mourning, but she also refers to herself as a secular Catholic and notes that Wojak brought Catholic iconography to their collaborative works.4 There is certainly a redemptive quality to the ritual that situates it within a long history, most specifically within the context of ritual in performance art. However, there is also a very private aspect to this collaboration: a pact or contract between the two women who were once lovers. McGregor is hepatitis C positive and in this sense, the blood she spills is ‘bad blood’, contaminated and diseased. As the two women come together at the climax of the performance, they do not touch. Wary of contamination, they turn away from each other and face the path of their own blood.

The shrouds worn by the female figures conjure up images of virgin brides and veiled women. The full-length garment can be seen as a white burka, but the translucent material reveals the bodies beneath. The mix of codes presents a powerful dichotomy. On one hand, the blood-letting for McGregor is redemptive, a quasi-religious absolution for her past sins, but in this instance, the spilling of blood conjures the draining of life from the bride(s), who traditionally promise to bring life into the world. The ultra feminine burka-like robes, which clearly show their sexualized bodies beneath, liberate the female bodies from their cultural confinements. The failure of the veils to conceal the bodies of the women was particularly pertinent in Poland, which McGregor describes as a profoundly homophobic society. The women literally bare themselves and yet they are not seen, their homosexuality is invisible.

As a solo artist, Fiona McGregor performed You Have The Body to an audience of one in Melbourne and Newcastle in 2009. In this intimate event, the viewer becomes a collaborator and brings the work to fruition. When I booked to see the performance, I was told that it was for one person at a time. On arrival, I am hooded and an attendant ties my hands behind my back. She leads me through a space: “turn left, turn right, walk ahead”. When we arrive at the destination, I am unbound and told I can take the hood off as the attendant leaves the room. Upon removing my hood, I see McGregor sitting before me in her underwear, her legs bound to a chair, her hands free and her lips sewn shut. Her eyes penetrate my gaze. Do I speak? She cannot. I am the judge and there is no jury. I stumble for words, retrace conceptual steps, ask banal questions knowing she cannot answer. I am aware that my questions may be stupid: I ask, is this a political statement? She nods to affirm. I want to pursue this but the artist is mute. Other people cried, which is in my opinion probably a more emotionally informed response. A relative dragged her from the room in dismay, wanting to save her. The intimate one-on-one performance is a challenging encounter. For me, the experience forced me to ask questions about my own identity as a human being and an art historian, and where the boundary lay. The experience taught me that in this situation, being less determined and more in tune with myself would have enriched my experience. I regret that I was not more open to the emotion of the encounter.

In Water # 2: Passage (part of Water Series, Artspace, 2011) McGregor is standing naked and wrapped in translucent medical tubes. Above her head, a saline solution drips into her vein, on the floor an empty bag waits to receive the blood from the cannula in her other arm. Blood slowly seeps into the tubes surrounding her body. It is moving slowly and not reaching the empty bag. Something has gone wrong. A medic stops the performance. Twenty minutes later, she returns. The audience is mostly backed against the wall: many are sitting down, anticipating the tattooing that is about to take place, as advertised. They seem to be unwilling witnesses, anticipating the pain to be endured by the artist. McGregor enters naked from the waist up, negotiates with a tattoo artist that she has employed for the performance and then proceeds to have herself tattooed in front of the audience. It is a painful experience. The tattooist stencils the outline of the tattoo onto her back—it is a drawing of an unfinished tapestry made by her great aunt before she died. Etched anew onto her great niece’s body with water rather than ink, its fleeting existence is marked again only to disappear. McGregor lays face down on a table awaiting the needles that will inject the water. She bites down on a napkin, grimacing and at times writhing in pain. There are occasional groans but it is the incessant high whining sound of the tattoo artist’s electrical tool that pierces the silence.

On the night of the performance, a video documentation was made and viewers could look into the video’s viewfinder to see the spectacular close-up images. But the live audience will also retain these vivid images in their memories. We watched both live and through the video: remediation was part of the event. Water #2: Passage was set within the context of a large installation which documented two earlier endurance works and the residue of three ‘live’ performances, of which it was one.

A video of Water #1: Descent is projected onto the wall and runs throughout Passage. Here we see the artist lying on a table with her body covered in salt. This table is in the room in which the tattooing occurs. Above her, a bladder of rainwater slowly drips onto her forehead. After five and a half hours the medical assistant stopped the performance for fear that McGregor would suffer from the extreme cold because her body was breaking down under the stress. Like in Passage, the performance involved salt and water. Salt is an erosive substance, but it is also part of the body’s chemical make-up. McGregor says the action was “an extended study of stillness and thirst; an image of torture, beauty and wastage.”5

One of the most interesting aspects of the exhibition was the relationship between the documentation of the live events, the endurance performances and the cathartic actions. What we are presented with in Water Series is a fairly large exhibition of documentation with the residue of the performance apparatus: the needles used by the tattooist, the surgical tubes wound around the artist’s body, containers of water and islands of salt with used napkins showing traces of the artist’s blood. Thus the performance/installation is as much about absence as it is about presence. Although the pain inflicted on the body is confrontational, the presence of the documentation—which proclaims an absence, a trace of the past—punctuates the space demanding to be viewed.

Fiona McGregor, Water #1: Descent, from Water Series, Artspace, 2011. Photo: Josh

Raymond.

Fiona McGregor, Water #1: Descent, from Water Series, Artspace, 2011. Photo: Josh

Raymond.

Ritual In Performance

In 2011, S.J Norman, an artist of mixed British and Indigenous Australian heritage with ties to both the Wannarua and Wiradjuri Nations, performed Corpus Nullius/Blood Country at Performance Space in Sydney. It was an intimate spectacle; the artist called it a meditation on “skin, violence, hoofed animals and Victorian parlour-craft.”6 The action involved the artist inscribing the word ‘Nullius’ across their breastbone with small pearl-headed pins, whilst embroidering the

word ‘Terra’ in red thread onto a raw sheep’s hide. Here the colonial land (terra), made rich on the back of a sheep, is juxtaposed with the incising of ‘native’ skin: the absent, nothingness that was ignored, neglected and abandoned in the nation’s history.

In Take This, For it is My Body (2010), Norman baked bread mixed with the artist’s blood and offered it to the audience in a one-onone performance. Although everyone who entered the performance space signed a disclaimer saying that they understood that they would be offered human blood to digest, very few declined to eat the bread. Bone Library (2012) addressed the artist’s cultural roots in an installation at Melbourne’s City Library. In this clinically archival work, Norman boiled and cleaned the bones of animals and then carefully inscribed them with words from the Woiwurrung language, now lost but once spoken by people of the Kulin Nation clans in the Melbourne area. In preparation for the performance, the artist said: “I was thinking about metaphors for language—language as the bones of culture and the way that the skeletal structure of an animal works and the similar function of language in keeping a cultural organism going.”7

S.J Norman speaks across languages, embracing the language of the body: its abject reactions and unseemly borders. At the same time, she welcomes people into these actions as intimate viewers or participants in real-time rituals. The work is poignant on both a human and a political scale. A tempo of one-to-one resonates into a larger context as the body and its affiliations filter back into the social community.

In 2006, a fair-haired woman sits astride a pile of forty dead squid with their eyes, tentacles, suckers and ink sacs intact.8 She is dressed in a pink felt suit layered over a suit that her father wore to weddings and funerals.9 The felt suit is also homage to Joseph Beuys’s Grey Felt Suit (1970).

I am watching a video-performance by Catherine Bell titled Felt is the Past Tense of Feel (2006). The performance was set in a town hall where the stage area was painted black so as to create a kind of void. The female figure and the squid are brightly lit and in the video, Bell proceeds to suck the ink out of each animal and spit it out over the suit until it is almost saturated in black. She rubs the ink over her hands and face and gathers all the forty squid bodies towards her, stuffing some inside the jacket and slowly shuffles backwards beyond the spotlights and fades to black. This endurance work lasts sixty minutes and is recorded in ‘real time’ on video with a static video camera.

Catherine Bell, Felt is the Past Tense of Feel, 2006. Courtesy of the artist et Sutton Galle-ry, Melbourne.

© Catherine Bell. Photo: Christian Capurro.

Catherine Bell, Felt is the Past Tense of Feel, 2006. Courtesy of the artist et Sutton Galle-ry, Melbourne.

© Catherine Bell. Photo: Christian Capurro.

The performance is primarily a cathartic and empathetic response to her father’s death. She says, “I imagine my father’s body dressed in the coffin. The outfit would be drenched by bodily fluids, just as the suit I wore for the performance is now stained and stiffened by the squid ink.”10 The outer felt suit was subsequently exhibited as a relic of the performance “to symbolize the ghostly presence of the father and evoke the stench of his body breaking down.”11 Bell says:

The squid work is about the public recognition of death as more than a funerary ritual controlled by religious and social protocol. Rather, it is an opportunity to publicly grieve and display emotion . . . risk, penance and endurance are prominent themes. The performance is analogous to shamanistic curing ceremonies devised to overcome a fear of death or the guilt of inflicting death.12

The autobiographical content of Bell’s Felt is the Past Tense of Feel is not immediately apparent to the viewer of the video. The catharsis and the abjection of the work are contained within the relation between the female figure and the dead animals. Although the video is silent, the physical action of sucking the ink induces disgust, as we see the artist making contact with each individual beak and we envisage the eye contact that must be taking place. Bell says: “I respond to the animal as if it is unconscious or recently deceased because the ink sacs remain active, waiting to squirt out involuntarily when handled. Sucking out the ink involved positioning my mouth over the squid’s beak and then our eyes would meet.”13

Theresa Byrnes is an Australian artist who has lived and worked in New York since 2000. She is a performance artist and a painter who sometimes uses the residue from her performances to create her paintings. Byrnes often paints with her whole body, creating ritual-like events that involve the body as the active agent of painting. She speaks freely about her work and her experience in terms of the feminine, nature and spirituality: “For me, painting is like church, or prayer, or a deep state of worship. It’s a communication with the Divine.”14 Carolee Schneemann draws parallels between the original abstract expressionists, Byrnes’ performance art/painting, and spiritual transformation:

Covered in viscous shining paint, drenched with color, Theresa Byrnes’ body becomes the agency of a visual, spatial transformation—marking, splattering, stroking surrounding surfaces. The effects are fierce and luscious, extending the radical marks of Kline, Pollock, and the dimensional implications of Abstract Expressionism. These physicalized events move between aesthetic principles of painting and sculpture as space is marked and concentrated by the physical activations of her body as medium.15

In The Measure of Man (2010), Byrnes is splayed out on a circular disk that is mounted vertically onto the back of a truck and driven through the Lower East Side of New York City. The artist, dressed in a scant white leotard, is rotated 360 degrees for a half hour. Black ink in the cavities of her costume oozes over her body and hair to create abstract paintings on a canvas on the floor of the truck. In Dust to Dust (2011), Byrnes emerges from a pit of brown mud and with great effort rolls and pulls her body along a stretched length of watercolour paper with the aid of two wooden bars on either side of the structure. Several ropes hang from above, allowing her to pull down paint pigments. A misting device extends the length of the paper, providing a wet surface to work on. The artist uses dirt placed into the troughs along the rails to add texture to the body painting. She also uses a pair of scissors to cut lengths of her hair, which are added to the painting. At the end she rolls into another pit of mud.16 As Joe Bendik notes: “These paintings provide a new definition of the term ‘action painting”.17

Byrnes has been widely acclaimed in the art world and in the mainstream press, but there is little serious art historical analysis of her work to date.18 The artist talks about painting as a reverie and suggests that she enters into an altered state. She clearly speaks to people looking for an alternative to rationality and the confines of a corporate world. Often, her performance works are overtly political, addressing issues of war and terror (Flag, 2002 and Fry Free, 2006), corporate greed (Tender, 2012) and ecology. The ritualistic and shaman-like qualities of Byrnes’ performances are enhanced for the audience through the endurance of the artist and her utopian spirit. Byrnes has a terminal illness and is confined to a wheelchair; in this context, her performance practice is painful and exhilarating both for her and for her audience. As an artist, Byrnes celebrates her body as one that has a unique range of abilities. Her medical condition allows her to push the boundaries of what it means to have a body—and what it means to be—in a particularly powerful manner. She addresses the ontology of the self in the world, making her work compelling and giving her licence to say what she believes.

Jill Orr has always been a cathartic performance artist and the spectre of the shaman is never far away. Interviewed in 1987, Orr said that her performances were like moments or glimpses that she had imagined, much like preconscious thoughts. Describing the performance process, she said: “There is a structure set up so that me, this body, can just be simply a vehicle of energy, that can go uninterfered with.”19 She also says that the actions are “exorcisms of fear.”20

Orr is an artist who speaks from the heart and engages with ecological and social issues as well as rites of passage and gender. She speaks out against discrimination, war, violence and society’s tendency to construct the Other as enemy. She has consistently put her own body on the line by exposing herself to danger and ridicule in order that people may come to assess their responses to these actions and thus to better know themselves.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters–Goya (Artspace, Sydney 2002) was Jill Orr’s cathartic response to the terrorist attacks in New York. In this performance, the artist went back to art history, specifically to the radical series of etchings made by Goya in 1799.21 The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters was a bloody performance in which tons of carcasses were strewn on the floor of the gallery. This was the raw material that Orr would work with for twelve hours. Dressed in a simple apron reminiscent of a medieval surgeon or butcher, Orr proceeded to bind the bones together creating distorted human and animal forms. This produced a bloody and smelly abstract narrative of bodies dancing in the dim light of the once clean gallery space. The bodies had been tortured and maimed: ugly, misshapen forms of life that presented the body as an abject horror.

The action was set against a series of paintings produced with light sensitive pigment that glows in the dark for a short period of time after it has been exposed to bright light. The paintings were gestural renditions of abstract bones. After making each of the bloody forms, Orr stood in front of the paintings, exposing herself and the canvas to an intense light for a few seconds, with the effect that ghosts of her body and the bloody creatures were etched into the surface. In the edited video of the performance this doubling was enhanced through special effects and a soundtrack reminiscent of a screeching body and technological collapse, as though these creatures were falling from a building.

Antipodean Epic (Mildura Palimpsest, 2015) is Orr’s most ambitious work to date in terms of scale and integration of video and live event. The on-site performance was filmed in the huge open spaces of a Mallee wheat field and a gypsum mine in Sunset Country and projected during the live performance.

On screen, Orr as bird-woman is buried under a mound of seed dumped on her from a huge harvester. She emerges from what must have been a painful experience and skips across a field of stubble. In the next frame she is seen tied by her hands and feet to a pole carried on the shoulders of two hooded men. The soundtrack is dominant in the video and incredibly loud during the live version. As the men slowly carry the prone bird body across the straight sun-kissed horizon, a strong digital pulse builds over a softer wind noise and an occasional bird twitter.

Jill Orr, Antipodean Epic-Interloper, 2015-2016. Photo: Christina Simons © Jill Orr.

Jill Orr, Antipodean Epic-Interloper, 2015-2016. Photo: Christina Simons © Jill Orr.

The unfolding narrative evokes seed, food production and genetic modification. The white coveralls worn by the men in the video are also given out to the audience to wear during the performance. They signify contamination either by the seed or the human, or both. Costume is used to dramatic effect in this performance. In the gypsum mine, a shamanistic figure performs a ritual in a white straw body suit and headdress, gesturing across a pale sandy landscape with the aid of two wand-like sticks. The following sequence shows the shaman coming over the horizon and crossing the threshold between day and night. Kicking up red earth as she advances towards us, she pauses as her image doubles. The soundtrack emphasizes the ritual aspect of the actions with a resonating gong. Behind the ghostly dance of the ‘strawman’, dark smoke arises from a raised metal sphere.22

The video performances were screened on the wall of a derelict railway shed where the old raised metal platform served as Orr’s live stage. The audience initially gathered in another location then walked across town dressed in hooded coveralls to the performance venue. After the first video, Orr as bird woman was spotlighted and winched off the platform high up to the ceiling. The lighting changed and the second video showed the strawman ritual in the landscape. Afterwards, Orr appears as the shaman figure, gesturing with her wand-sticks as she moves along the platform. At a designated spot, she stops and removes the straw costume and headdress. Now in a short bodysuit, she stands whilst an enormous amount of cold water

is poured on her head from above. This elicits slow rapturous movements from the artist–observers could imagine how these moments were being transformed into video and still photographs throughout the performance. After this baptism or transcendence ritual, Orr continues to the end of the platform and walks down onto a large circle of grain. She lies down at the centre and the audience does the same until the circle is filled with white hooded bodies surrounding the artist.

Whilst the performance has a political narrative about the ecology of food production, it also has a strong poetics. It asks us to be curious about other ways of understanding. Orr, embodied as shaman, shows us strong performances of otherworldly characters crossing thresholds, moving across the horizon of a world. We are asked to welcome them and interpret their messages. The work gestures to cosmology, the immensity of the land and something ancient and forgotten, but it also offers human scale and significance. The languages of ritual, shamanism, and magic resonate throughout.

Drawing on major social upheavals and responding quickly to them, Orr offers herself up as an in-between body, a self or energy “that can go uninterfered with.”23 Postmodern critics may well see this as a romantic gesture, but it is certainly a position that resonates with the role of the shaman.

Performance Actions and Interventions

In Australia, John Howard—the nation’s second-longest-serving Prime Minister (1996-2007) and a key figure in parliament throughout the postmodern period—was famous for inciting the rights of ‘ordinary’ Australians to be ‘relaxed and comfortable’, whilst he and his government took care of business.24 This included the war on Iraq, draconian industrial relations reforms, the escalation of increasingly shameful immigration policies that saw many innocent refugees detained in prison-like conditions and the eroding of the human rights of Aboriginal Australians. Although John Howard publicly denounced postmodernism during the history wars and debates over school curricula, it is arguable that he embraced the anesthetized state of his constituents.25

In response to Howard’s immigration policies, Mike Parr presented a series of performance works, some of which utilized a live webcast. Edward Scheer states that “Parr has consistently placed his live artwork in a dialogue with recording technologies.”26 His videos, photographs and webcasts “reflect the liveness and immediacy” of the work and “the way Parr uses them to feed into other experiments and projects means that they can never slip into the quiet retirement of documents.”27

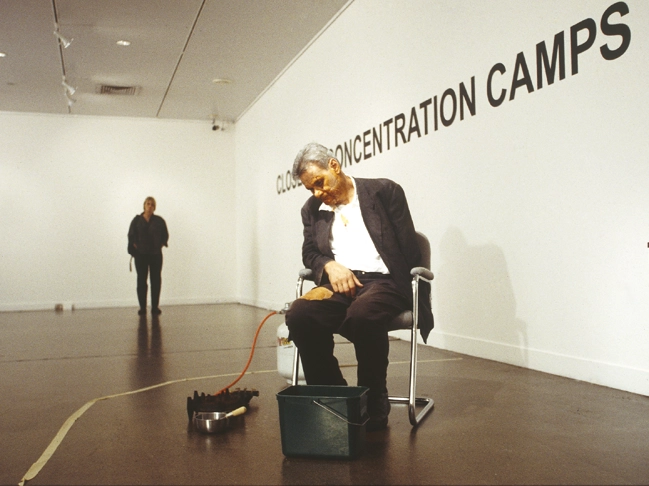

Close the Concentration Camps at Monash University Museum of Art (15 June 2002) was presented live and broadcast via webcast for the five-hour duration of the event. The audience and the remote screen viewers saw a man sitting slumped in a chair; he wore a black suit, white shirt and no tie. His right trouser leg was ripped across the thigh revealing the word ‘ALIEN’ branded into his skin. During the course of the performance, the artist’s lips, eyes and ears were sewn together, rough surgical sutures criss-crossed his face, blood and iodine solution ran from the wounds onto his white shirt. Parr could not speak and his vision was impaired. Before him a huge mirror reflected the viewers in the museum, most stood back against the clean white walls, secondary witnesses to the trauma enacted on the artist’s body.

© Mike Parr Close

the Concentration

Camps, 6 hr performance,

Monash

University Museum

of Art, Melbourne,

15 juin 2002.

Performer: Mike Parr.

Photographers:

Paul Green,

Felizitas Parr.

16mm camera:

Mark Bliss, Sound:

Tiegan Kollosché.

Video Systems:

courtesy Monash

University Museum

of Art. Photo:

courtesy of the artist

© Mike Parr Close

the Concentration

Camps, 6 hr performance,

Monash

University Museum

of Art, Melbourne,

15 juin 2002.

Performer: Mike Parr.

Photographers:

Paul Green,

Felizitas Parr.

16mm camera:

Mark Bliss, Sound:

Tiegan Kollosché.

Video Systems:

courtesy Monash

University Museum

of Art. Photo:

courtesy of the artist

The text along one wall incited Australians to CLOSE THE CONCENTRATION CAMPS. In a separate room, excerpts from Not the Hilton: The Immigration Detention Centre Inspection Report of 2000 were projected onto the walls. Parr’s action was an empathetic gesture, in recognition of the trauma experienced by ‘illegal’ immigrants who were, at the time, sewing their lips shut as a protest against their prolonged incarceration.

The audience in the museum heard the burning gas jet and felt the heat of the flame as the artist warmed the branding iron. They smelt the burning flesh when he branded his thigh. If they arrived early

enough they watched each suture being sewn into his face by his wife, Felizitas. People were free to roam about from one room to the next. They were also free to discuss the performance and to measure their own responses with others, a community formed around the horror enacted by the artist. There was a sense of mourning and disbelief that we could inhabit a country in which such atrocities continue to take place. Everyone shared the nation’s shame.

The webcast experience was different from the live event. Firstly, there was a slight delay and a flickering as the live feed caught up with itself. The performer appeared to move in slow and jerky movements. Secondly, the aspect of presence, which has been a grounding principle of much performance art, was challenged and erased by the televisual structure. Adam Geczy argues that this remediation through the screen flattens the live event and “the viewer becomes more like a voyeur, protected by distance.”28 This viewer can watch the body in pain and just keep doing whatever they like: washing dishes, ironing clothes, having sex, eating, drinking or watching another television screen. In short the viewer can be and often is disengaged.29

In Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, Oi, Oi, Oi (Democratic Torture) at Artspace in Sydney (2-3 May 2003) Parr again had his face sewn up. Dressed in a black suit with a small replica Australian flag attached to the stump of his left arm, he sat in front of a wall of projections of news reports of the invasion of Iraq.30 After twenty-four hours, electrodes were attached to his face and those watching the webcast were able to administer electric shocks for the remaining six hours of the performance. Edward Scheer notes that: “Parr received approximately 25 shocks before the server crashed under the strain of the number of electric shocks.”31

© Mike Parr

Aussie, Aussie,

Aussie, Oi, Oi, Oi

(Democratic Torture),

30 hr performance,

Artspace,

Woolloomooloo,

NSW, 2-3 mai 2003.

Performer: Mike Parr.

Photographers:

Paul Green,

Felitizas Parr,

Dobrila Stamenovic.

16mm camera:

Mark Bliss. Sound:

Tiegan Kollosché.

Video: Adam Geczy.

Co-performer:

Felizitas Parr and

internet audience.

Photo: courtesy

de l’artiste.

© Mike Parr

Aussie, Aussie,

Aussie, Oi, Oi, Oi

(Democratic Torture),

30 hr performance,

Artspace,

Woolloomooloo,

NSW, 2-3 mai 2003.

Performer: Mike Parr.

Photographers:

Paul Green,

Felitizas Parr,

Dobrila Stamenovic.

16mm camera:

Mark Bliss. Sound:

Tiegan Kollosché.

Video: Adam Geczy.

Co-performer:

Felizitas Parr and

internet audience.

Photo: courtesy

de l’artiste.

What is evident in Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, where Parr gives the distant audience the chance to intervene, is that they are happy to play the part of sadistic torturer and inflict electric shocks on a body that is already in pain. By the time the audience was able to interact, Parr’s body, which had been motionless for twenty-four hours, was showing signs of exhaustion and physiological distress. His body was incredibly swollen due to fluid retention so that when he was shocked he shook like a jelly.32 Yet the distant audience happily took on the role of perpetrator and used the artist’s body as a corporeal site to enact atrocities. The audience is so distracted from the real that they are anaesthetised to the pain of the other.

Working solo and in collaboration, Deborah Kelly addresses issues of race, sexuality, national borders, histories of place and disruption. She uses the internet and social networking to generate political protest with people signing up to perform actions around the nation and sometimes the globe. Tank Man Tango was performed in twenty cities and towns across the world on June 4, 2009 as a memorial to the Tiananmen Square protests in China. As Kelly explains, It was for those who would remember; to give it shape, duration, experience and ritual. It’s a memorial for the protests, and for the murdered protestors, rather than for that one person, the symbolic tank man. The work paid homage to fighting tyranny… It hoped to bring life to history… Dancing the memorial was a way to be, to act, in a city or a town, to make a public sphere, to be an agent in it. It sought to diminish the distances between people in space and time, to connect us with those that struggle, and to build culture around us.33

Deborah Kelley, documentation of Tank Man Tango, a Tiananmen Memorial, in Sydney, 4

June 2009. Photo: William Yang.

Deborah Kelley, documentation of Tank Man Tango, a Tiananmen Memorial, in Sydney, 4

June 2009. Photo: William Yang.

Kelly spent hours looking at the famous footage of the man who stood before the advancing column of military tanks after the massacre at Tiananmen Square.34 As the tanks tried to move around him, he waived two plastic shopping bags to ward them off. At one stage he climbed on top of one of the tanks and tried to talk to the driver. At that stage the tanks all turned off their engines and the man climbed down. When they started the engines again, he resumed his protest, moving this way and that, blocking the might of the state with his shopping. He became an international symbol of courage against tyranny.

Working with the choreographer Jane McKernan, Kelly created Tank Man Tango and posted the video of performance artist Teik Kim Pok dancing the steps onto YouTube. The footage included a short narration which ended by inciting people to “forget to forget” and do the tango on June 4th 2009.35 There are numerous versions of the dance now available on the internet with dance instructions in various languages.

Kelly has also worked in collaboration with the art collective boat-people.org, which has systematically created public performance events and installations to bring attention to the repressive policies of successive Australian governments concerning immigration.36 The group includes Safdar Ahmed, Zehra Ahmed, Stephanie Carrick, Dave Gravina, Katie Hepworth, Jiann Hughes, Deborah Kelly, Enda Murray, Pip Shea, Sumugan Sivanesan and sometimes Jamil Yamani. Their first intervention was to project a huge image of a tall ship reminiscent of those of the First Fleet onto the sails of the Sydney Opera House during the controversial federal election campaign in 2001, which was clouded by issues of asylum seekers and border protection.37 Beneath the image of the ship were the words BOAT PEOPLE, pointing to the fact that all non-Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander peoples living in Australia had arrived from elsewhere, many by boat. After the event, 50,000 postcards of the tall ship image were distributed free throughout cafes in Sydney.

In 2004, boat-people.org invited others to participate directly by creating a living memorial to the 353 people who drowned in 2001 when a boat carrying asylum seekers sank.38 People in Melbourne gathered on the banks of the Yarra River to have their bodies whitewashed ready for the projection of images of the disaster, including pictures of the dead collected from family members who had survived. In response to another federal election campaign in 2010, boat-people.org invited people to join a public protest by wrapping their heads and faces in replicas of the Australian flag to represent the ways in which people are blinded by nationalism. People were simply asked to congregate alone or in pairs and groups and to take photographs and videos and send them to an e-mail address. The anonymous remote public participation was overwhelming, as people sent in images of themselves congregating in parks, civic centres and on the beach. All were muffled by the tyranny of nationalism that was writing people into a history with which they did not relate. There is no doubt that this protest went quietly viral as people took up the protest in their own ways. They organized their own groups or went to sites suggested by boat-people.org or others.

These initiatives can be likened to flash mobs but they have a political intent. They use the same means of production and distribution, but they ask people to take a stand on specific issues. The events are a clear demonstration that Australians are engaged but disillusioned with democracy and its consensus politics. Kelly does not know all the people who contribute to her events, she simply works with boat-people.org to create possible scenarios for political protest. The success of Tank Man Tango throughout Europe, North America and Asia is a testament to a methodology that provides a platform but does not cajole the participant. The choice of whether to participate is left to the individual.

Kelly and boat-people.org are contemporary examples of activist artists who can trace their legacy to like-minded artists in the 1960s and 1970s. Kelly cites the North American art activist Martha Rosler as a mentor. Although her practice is part of a twenty-first century revival in socially concerned event-based art, she resists the term relational aesthetics because she has witnessed the recuperation of much of this work in contemporary museums and on the biennale circuit.39

Ash Keating has often been described as an environmental artist because one of the signatures of his practice is to work with large quantities of industrial waste material to raise people’s awareness of the ecological consequences of ubiquitous consumption. This began with early solo performances, such as Escape from Tag Mountain (Seoul, Korea, 2008) where he scanned the streets to find commercial labels, which he collected into a huge mountain within which he was buried. The action consisted of him slowly emerging naked from the trash of labels and tags. Here the fragile human body emerges as if re-born from the soft rubble of consumer culture’s branding.

Ash Keating, Escape

from Tag Mountain,

2008. © Ash Keating.

Ash Keating, Escape

from Tag Mountain,

2008. © Ash Keating.

Reuben Keehan observes that Keating has two performance persona: “the besuited Everyman… and an amorphous waste monster.”40 The most engaging Everyman performance involved the artist exploring what he calls the “human undoing of machine production.”41 For 250-hours—Work for 1 Person / Press Release (2005-07), Keating intercepted the distribution of the mX newspaper over a period of one week. mX is a trashy tabloid distributed free to public transport commuters in Melbourne who then discard their copies. Keating transported the six thousand copies he had procured to his studio and took out one page from the Tuesday edition that had a photograph of the endangered Australasian garnet bird. He then carefully cut the figure out and later performed a series of actions where he released the tiny birds. The labourious task of stacking, selecting and cutting was filmed and shown at a fast speed alongside the slow release of the birds into the air.

Activate 2750 (2009) was one of Keating’s largest participatory interventions. Part of a C3West Project in Western Sydney established to broker closer relationships between artists and businesses, Activate was a collaboration between Keating, the waste management company SITA Environmental Solutions and local artists and performers.42 Ten tonnes of clean, reusable resources were salvaged from the local Davis Road Transfer Station over a two-week period and transported to the Penrith City Civic Precinct in the centre of town.43 This pile was then re-sorted and carefully re-constructed. Two rings of fencing were installed around the installation. A safety fence and a containment fence which Keating says, “created a kind of human rat-run that was integrated into the evening performances. The fencing also reinforced the atmosphere of the installation as a kind of apocalyptic zoological habitat.”44 The residency in Penrith aimed to raise people’s awareness about the amount of rubbish that goes into landfill each year by activating processions of ‘waste creatures’ in the streets and shopping centres, including performances of The Uprising by a troupe of local Krump dancers.45 The Westfield Processions entailed each participant pushing abandoned supermarket shopping trolleys full of reconstituted waste with a soundtrack composed by Vincent O’Connor that incorporated the noise of the compacting machines used at the Davis Road site. They appeared as alien presences in a macabre ritual on escalators, in atriums, in shopping malls and along the streets encountering shoppers, motorists and passers by. The processions for Activate were initially intended to be festive, conjuring the atmosphere of a carnival but Keating says they “ended up more like a funeral procession.”46 This aspect can be seen throughout the re-workings of waste material into monuments and memorials. Amelia Barikin writes about the melancholia and mourning involved in seeing a ritual process that harnesses attention towards an apocalyptic future. This was most apparent in the final sequence of Activate where the ‘waste-creatures’ slowly returned to the mountain of refuse to be absorbed into their tomb-like habitat. Keating’s works are always labour-intensive and time-based.

The waste used to create them is recycled back into the wastemanagement system, so no lasting objects are produced. But what remains for gallery display is the sophisticated, professionally produced time-lapse photography and video documentation. Although there is now a trend to make documents of events that never had a live audience, there is also a critical melancholy for the act itself.47 This can be viewed as a longing to return to the ontology of performance (the idea that one had to be there to really experience performance) that Peggy Phelan campaigned for during the height of the liveness debates.48 Keating’s works live on through their documentation as they become remediated as second-degree works in their own right, but their existence in public space is paramount. Keating says his aspiration is to effect change through art.49 A central part of this is intervening in the metropolis with works that speak broadly to ecological issues that affect consumer society.

Conclusion

The dialogue around the remediation of performance art, which I touched on briefly in this paper, tells us a lot about what performance is. Peggy Phelan’s thesis about the ontology of the live act is pertinent, but it needs to be taken in context; it cannot be universalized across the discipline. Increasingly, we are seeing performance made for video or the Internet; these works need to be analyzed as part of the continuum of performance art practice.

On one hand, body art is often visceral, involving blood, excrement and tears. In its remediated form, a distance is created so that the viewer does not need to encounter the real. This is a problem when we are considering radical art. If I am alone in my living room and a man appears on a screen through a social networking site and I am told he is wired for pain, how many times do I prod him? In this instance, the remediated environment is clean, safe and distanced. It allows us to turn off our responsibilities. It allows us to act as though we were not citizens of the world. But what happens when participatory performance practice embraces the Internet and is used to address personal and political issues? Here we have a mediated performance that is inclusive and harnesses the potential of the Internet to connect people across the globe. In some instances, these connections between people have highlighted the intimacy of reception that is built into the Internet. On the one hand, the Internet can stress surveillance and distraction, while on the other, as it is beamed into individual personal computers in our homes, it can create a platform for intimate exchanges.

The issue of performance made exclusively for the video screen is another form of mediation. It is certainly true (following Phelan) that onscreen performances are less visceral, but it is also clear that some artists prefer this medium and/or are making video versions of live events to be placed into museum collections. Although such practices shift some of the original claims of radical performance, it is clear that senior artists like Mike Parr and Jill Orr embrace the possibilities of new media as a way of extending their practices. It is also apparent that any remediation of live art actions nurtures art history. It is easier to reconstruct works that we have not seen first hand when there is a lasting record. That said, I am still a fan of the concept of a performance that never happened and that only exists as a rumour. Anne Marsh is Professorial Research Fellow at the Victorian College of the Arts in Melbourne, Australia. Her most recent book is Performance_Ritual_Document published by Macmillan in 2014.

Most of this essay is extracted from the book with some updates for works after 2014.

2 Fiona McGregor, Strange Museums, p. 14.

3 Arterial–Scroll (blood on photographic paper, 3000x150) was a finalist in the Blake Prize in 2007.

4 Fiona McGregor, Strange Museums, p. 175.

5 www.fionamcgregor .com/actions/water-1 [accessed May 1st2019]

6 www.sarahjane norman.com/#! master-page-6, [accessed May 1st2019]

7 Liza Power, ‘Songs of Social Cohesion’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 19 May, 2012.

8 Bell explains that she commissioned a com- mercial fisherman to individually line catch large specimens and keep them intact so as to increase the cathartic affect. See Catherine Bell, Liminal Gestures: Ritualising the Wound through Performance and Lived Experience, PhD thesis in the Department of Fine Arts, Faculty of Art & Design, Monash University, 2007, p. 130, n. 18.

9 It is the suit her mother first chose to bury her father in but her siblings resisted the decision and he was buried in casual wear. Catherine Bell, Liminal Gestures, p. 126-7.

10 Catherine Bell, Liminal Gestures, p. 127.

11 Catherine Bell, Liminal Gestures, p. 127.

12 Catherine Bell, Liminal Gestures, p. 132.

13 Catherine Bell, Liminal Gestures, p. 127.

14 Carey Monserrate, ‘A Date with the Divine: The Art of Theresa Byrnes’, Cross Currents, 54:4, Winter 2005, p. 138.

15 Carolee Schneemann, as quoted on Theresa Bryne’s website: www.theresabyrnes. com (accessed September 17th 2012).

16 See www.theresa byrnes.com/ performances. asp?p=16 (accessed September 17th 2012).

17 Joe Bendik, ‘Suffer For Your Art: Theresa Brynes doesn’t take the easy way out’’, Chelsea Clinton News, February 24, 2011, p. 4. Also posted on www.theresa byrnes.com/press. php?p=26 (accessed September 17th 2012).

18 Her solo shows New York to Sydney (New York and Sydney, 2006) and Changelings (2008) at Saatchi and Saatchi in New York and Sydney confirm her standing in the field.

19 Jill Orr taped interview with the artist, 24 June, 1987.

20 Jill Orr taped interview with theartist, 24 June, 1987.

21 The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters is the title of one of Goya’s etchings from the series Los Caprichos (first exhibited in 1799). The series presents a bitter critique of the Spanish aristocracy, the clergy and human nature and covers topics such as child sexual abuse, witch- craft and prostitution. See www.eeweems. com/goya/sleep_ of_reason.html [ac- cessed May 1st2019].

22 In the photo sequence Jill Orr titles this figure ‘the strawman’. See https://jillorr.com. au/e/antipodean-ep- ic---strawman--sec- tion-two- [accessed 1 May 2019]

23 Jill Orr taped interview with the artist, 24 June 1987.

24 John Howard was Member of House of Representatives 1974- 2007, Treasurer in the Fraser Government 1977-1983, Leader of the Opposition 1985- 1989 and in 1995.

25 The history wars are an ongoing debate concerning the interpretation of Australia’s colonial history and its impact on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander first nation peoples. See Stuart Macintyre (with Anna Clark), The History Wars, Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 2003, Robert Manne (ed.), White- wash: On Keith Wind- schuttle’s Fabrication of Aboriginal History, Melbourne: Black Inc., 2003 and Keith Wind- schuttle, The Fabri- cation of Aboriginal History, Volume One: Van Diemen’s Land 1803-1847, Sydney: Macleay Press, 2002.

26 Edward Scheer, The Infinity Machine: Mike Parr’s Performance Art 1971-2005, Melbourne: Schwartz City, 2009, p. 109.

27 Edward Scheer, The Infinity Ma- chine, p. 109.

28 Adam Geczy, ‘Mike Parr: Internet Performance’, Realtime, 52, p. 2. www.realtimearts. net/article/52/6946. Accessed 1 May 2019.

29 Adam Geczy, ‘Mike Parr: Internet Performance’, Realtime, 52, p. 2.

30 Parr was born with a disfigured arm, which was subsequent- ly amputated.

31 Edward Scheer, The Infinity Ma- chine, p. 127.

32 Mike Parr, in corre- spondence with the author, 21 May 2012.

33 www.australianstage.com. au/200909092831/ features/sydney/deb- orah-kelly.html ac- cessed 6 March, 2013.

34 The massacre took place on June 4 and the tanks rolled in the following day when the protest of the lone man occurred (5 June 1989). All images taken by Western journalists of the event were sup- pressed on Google.

35 www.youtube.com/ watch?v=lQW8m- 8MctsU accessed 1 May 2019.

36 See www.weaus- tralians.org/artists/ boat-people-org/, accessed 1 May 2019.

37 John Howard was returned to power for his third term as Australian Prime Minister in October 2001. MV Tampa—a Norwegian ship car- rying over 400 asylum seekers rescued from a distressed fishing vessel in international waters—was refused entry to Christmas Island on 29 August 2001, generating one of the most contro- versial incidents in Australia’s recent his- tory. For a compelling account see David Marr and Marian Wilkinson, Dark Victo- ry, Crows Nest NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2004.

38 Following the Tampa incident, the SIEV-X sank on 19 October 2001. SIEV stands for Suspected Illegal Entry Vessel. See Tony Kevin, A Certain Maritime Incident: The Sinking of SIEV-X, Carlton: Scribe Publications, 2004.

39 E-mail correspon- dence with the author 20 January 2013.

40 Reuben Keehan, ‘Double Agents: Complication in Recent Performance’, Art & Australia, 47:1, Spring 2009, pp. 156-153.

41 Ash Keating as quoted in Ulanda Blair, ‘ANZ Private Bank and Art & Australia Con- temporary Art Award’, Art & Australia, 46:1, Spring 2008, p. 176.

42 C3West is an initiative of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney established in 2006. See MCA Learning Resource: C3West: Contempo- rary Art Community Commerce, pdf available on-line at: www.mca.com. au/media/uploads/ files/C3west_Learn- ing_Resource.pdf Accessed 17 March 2013.

43 The numerals in Keat- ing’s title refer to Pen- rith’s postcode: 2750.

44 Ash Keating, ‘Acti- vate 2750’ in MCA Learning Resource: C3West: Contempo- rary Art Community Commerce, p. 27.

45 The dancers were: Darrio Phillips aka Manifest, Kon aka J. Manifest, Yasim aka J. Krucial and Omar aka Scrappy.

46 Ash Keating as quot- ed in Amelia Barkin, ‘Time Shrines: Melan- cholia and Mourning in the Work of Ash Keating’, Discipline, 2, Autumn 2012, p. 20.

47 Reuben Kee- han, ‘Double Agents’, p. 150

48 See Peggy Phelan, ‘The Ontology of Performance: Rep- resentation without Reproduction’ in P. Phelan, Unmarked: The Politics of Performance, New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1993, pp. 146-166. For an over- view of the liveness debates see Anne Marsh, Performance_ Ritual_Document, South Yarra: Macmil- lan, 2014, pp. 23-49.

49 Ash Keating, in con- versation with the au- thor, 16 October 2012. Art Action

© 2025 professor ANNE MARSH | SITE BY jamie charles schulz