r e a:

belonging and

becoming

Installation

2024

r e a:

belonging and

becoming

The easiest and the most “natural” form of racism in representation is the act of making the other invisible. —Marcia Langton1

Native, 2013/24, and Native (yugal/song), 2024, are complex and multilayered installations by r e a that invite and perform ideas of belonging and becoming in a poetic critique that prioritises the voice over the sign. They untangle the knot of representation and agency and the entwining of language and identity. In the history of First Nations people the loss of language and dialect is primary. To lose one’s birth language, or never to know it, is a fundamental loss in terms of being and becoming. What is my culture? Without my language, how can I tell you who I am?

An acknowledgement of the primary function of language runs throughout societies. This is why immigrant parents teach their children their “native” language; it is what keeps Greek, German, Chinese and other bilingual schools going throughout our cities. But until very recently there was little acknowledgement that Aboriginal Australia needed these services. Historically, Australian “native” tongues were not welcome in the colony, so they were wiped out, silenced, forgotten. Speaking about her experience, r e a said in a 1998 interview:

I don’t relate to the English language . . . I find it a very oppressive language. I find it a very obnoxious language. And I find it also a very restrictive 15 language—a language that doesn’t provide a framework for an Aboriginal person. But for me, because I don’t have my own Gamilaraay language, I can’t actually work within my people’s language to even turn that language into a translation of English that people can understand. I don’t have that. I only have the body feelings and the thoughts and that’s why I do the work I do, because that’s about the language for me.2

Today there is a national revival of Indigenous Australian languages, and it is becoming easier to find elders and descendants who are teaching those dialects which have survived and been translated from oral languages into spoken and written word.3

Native, 2013/24, is informed by r e a’s earlier work Native. In 2013 r e a and other artists participating in the Australian Indigenous Artist Residency at the Blacktown Arts Centre on the site of the Native Institute, came across this problem of language and culture while working with the descendants of the Darug/Dharug people of that region. Artists came into the program with diverse cultural knowledge about language and Country and found themselves experiencing their own intergenerational trauma in response to the site. They each needed to navigate experiential territories and cultural differences to find a way to respond that was both politically relevant and culturally respectful. “It was about being respectful while giving the topic the voice that was due,” r e a said.4 This involved deep listening. The original custodians of the land on which the Blacktown Native Institute stood had ample reason to guide the kind of representations that could be made because these would become part of a continuing history.5

This issue about language—who speaks it and who owns it—is fundamental throughout the Western canon of philosophy and more recently feminism and critical theory. Ironically, the language issue is likely to be seen as a failure of postmodernism and poststructuralism, both of which put great faith in language, declaring that “language speaks the subject” and thus in many people’s minds foreclosing on human agency.6 This was the point of these theories, to dismantle and deconstruct social norms, but their prioritisation of social construction over lived experience had the effect of silencing the other—especially women and minorities who felt that, yet again, they had been marginalised and their experience denied. Whatever the academic complexities of the arguments, and there are many, it wasn’t washing well on the coalface.

As part of Native 2013 r e a installed a portable, digital road sign on the site of the Blacktown Native Institute with the word ‘native’ appearing in big letters. It was a sign, a proclamation in the language of the oppressor, the language of colonisation. (It is revisited in a different format for the 2024 installation.) The display included other words that had been re-invented by the artist, word plays such as ‘Rekon-silly-nation’. The words were outside, signs for things, ideas, ideologies. They are part of the “Symbolic” field, the “Law of the Father” in a Western psychoanalytic tradition.7

r e a, Still image from Native 2013

r e a, Still image from Native 2013

r e a, Still image from Native 2013

r e a, Still image from Native 2013

“Native” is a word consumed by white colonial philosophical and anthropological interpretation. It is an example of how language writes “the subject”, the person or the people to whom it is deemed to apply. To be “native” in the Western enlightenment tradition was to be closer to nature, further away from civilisation. To bring the “native” into “civilisation” in the nineteenth century was seen as “white man’s burden”, part of an imperialist/colonial program of “manifest destiny” in which white people are perceived as superior in all aspects of being.8 The realisation of this ideology was made possible through institutions such as the Blacktown Native Institute, established “as part of a campaign, led initially by Governor Lachlan Macquarie to extend enlightenment ideals to the indigenous peoples of the Sydney colony”.9 Christian churches, with their missionary zeal, were the pedagogical and “spiritual” enforcers of the re-education programs that supported this ideology. Martin Nakata has spent his career unpicking the complexities of the enlightenment position as it developed in anthropology and explaining how Indigenous peoples became the object of study as Western philosophy became intent on tracing the origins of the species via intensive studies of the “native”.10

r e a, Still image from Native 2024

r e a, Still image from Native 2024

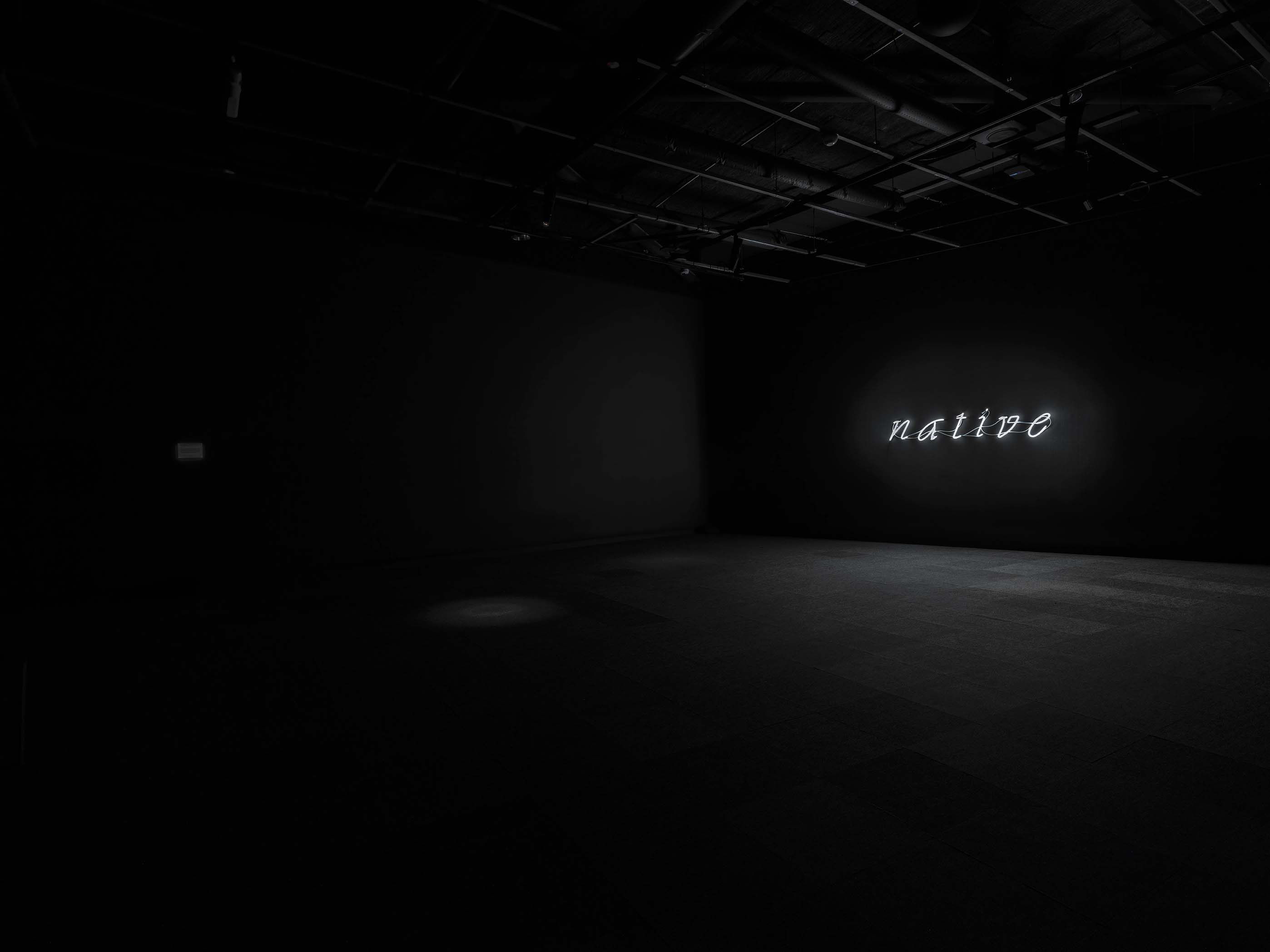

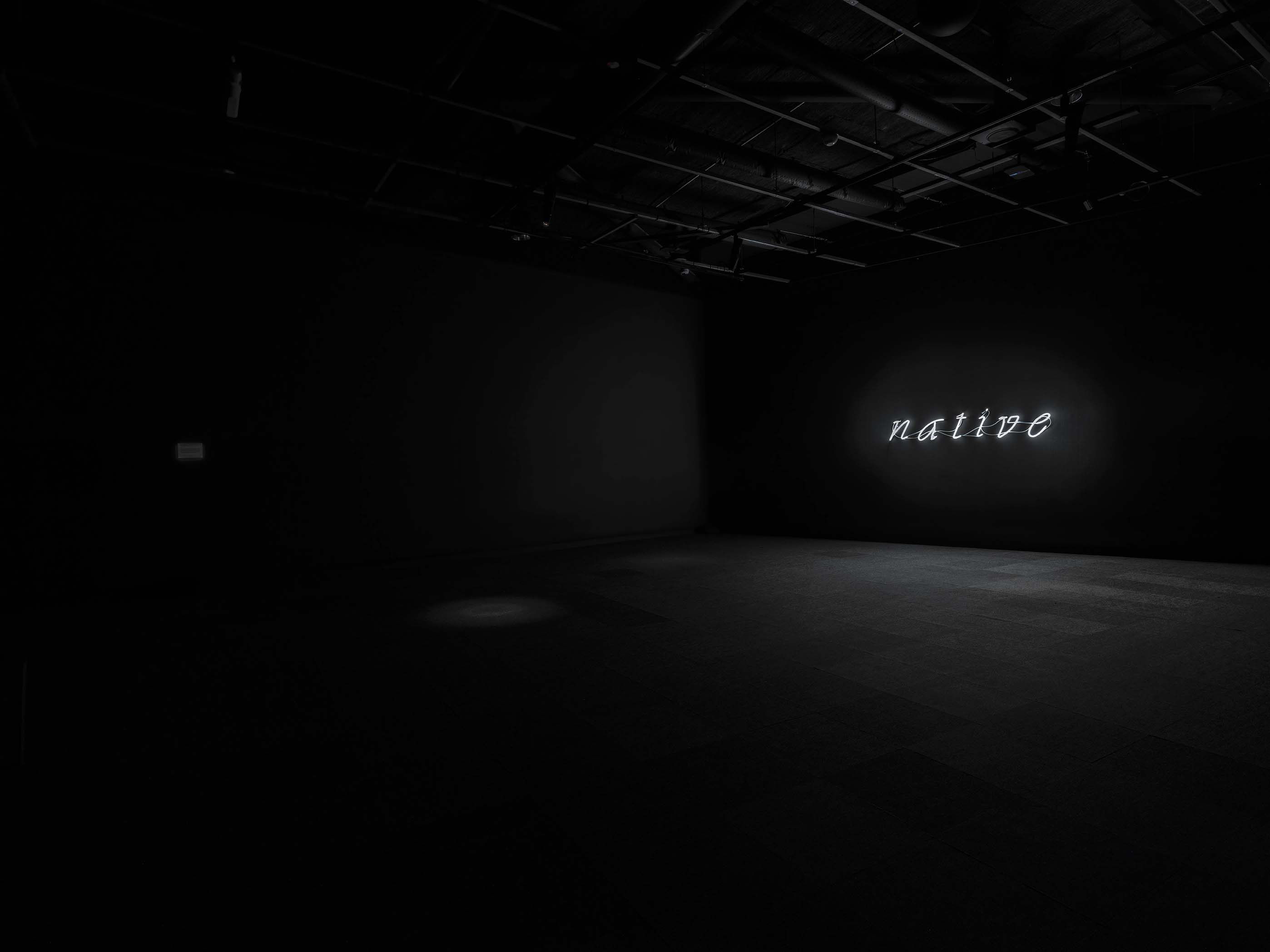

In the current exhibition r e a: NATIVE, r e a has revisited their first iteration of Native, 2013, to further expand on its use of language, sound and moving image and offer a new culturally sensitive experience. As the visitor walks into the gallery, they encounter subtle lighting and a neon sign with the word ‘native’ written in white light across a black background. The installation is without the original church pew and r e a has remixed the soundtrack. As viewers move through the space lit by the neon sign their individual bodies trigger hidden directional speakers. The Mount Druitt Indigenous Choir sing softly in their language of Darug/Dharug as another group of children read excerpts from various historic texts drawn from Australian literature, film, songs and political speeches that have “represented” or addressed the ongoing conversation around Aboriginal identity and history and who belongs where. The voices of the children take up space in their physical absence, creating a tender strength that challenges the ominous sign. Four young voices alternate in reading the script (excerpted here):

Treaty.

Lay down the stone axe take up the spear.

Let us turn the page together and write the new chapter in our nation’s story together.

Blacktown Blacktown, 1823.

Black boy black boy the colour of your skin is your pride and joy.

The Native Institute 371979915.

We are learning how to see Australia through Aboriginal eyes.

No more boomerang, no more spear, no more corrobboree, now all civilised.

This land was never given up.

This land was never bought and sold.

Apology in the spirit in which it is offered is part of the healing of the nation.

A land of sweeping plains, of rugged mountain ranges, of drought and flooding rains.

The town of Parramatta, 1814.

No more boomerang, no more spear.

We have committed ourselves to succeeding in the test which so far, we’ve always failed.

We take this first step by acknowledging the past and laying claim to a future that embraces all Australians.

Let us turn the page together and write the new chapter in our nation’s story together.

[Each child asks individually:]

We fail to ask: how would I feel if this were done to me?

We fail to ask: how would I feel if this were done to me?

We fail to ask: how would I feel if this were done to me?

We fail to ask: how would I feel if this were done to me?11

In another life the Aboriginal children in this group may well have been taken away from their families and placed into “care” at the Blacktown Native Institute. There they would have been “trained” to do menial work. Their families would have been broken, their history shattered, their culture torn from them. These children know this pain even though they didn’t experience it directly because intergenerational trauma is a reality for all Aboriginal people. These children have relatives who were stolen and broken.

The first encounter in the gallery makes the split between language and culture as experienced by contemporary Aboriginal people come alive for the visitor. In the background the singing in Darug/Dharug language envelops the voices of the children who read in English. This tenderness washes through the space on the soundwaves.

When r e a said in 1998 that “I only have the body feelings and the thoughts and that’s why I do the work I do, because that’s about the language for me”, they may well have been forecasting Native, 2013/24, in their imagination. In their PhD thesis they worked through the methodology of the research and how language and feeling are different. In it, there is a profound recognition and respect for Country, for going home, for being and the revelation of belonging, even though they didn’t have the language. Here reigns the language of the mother, the body and the land.

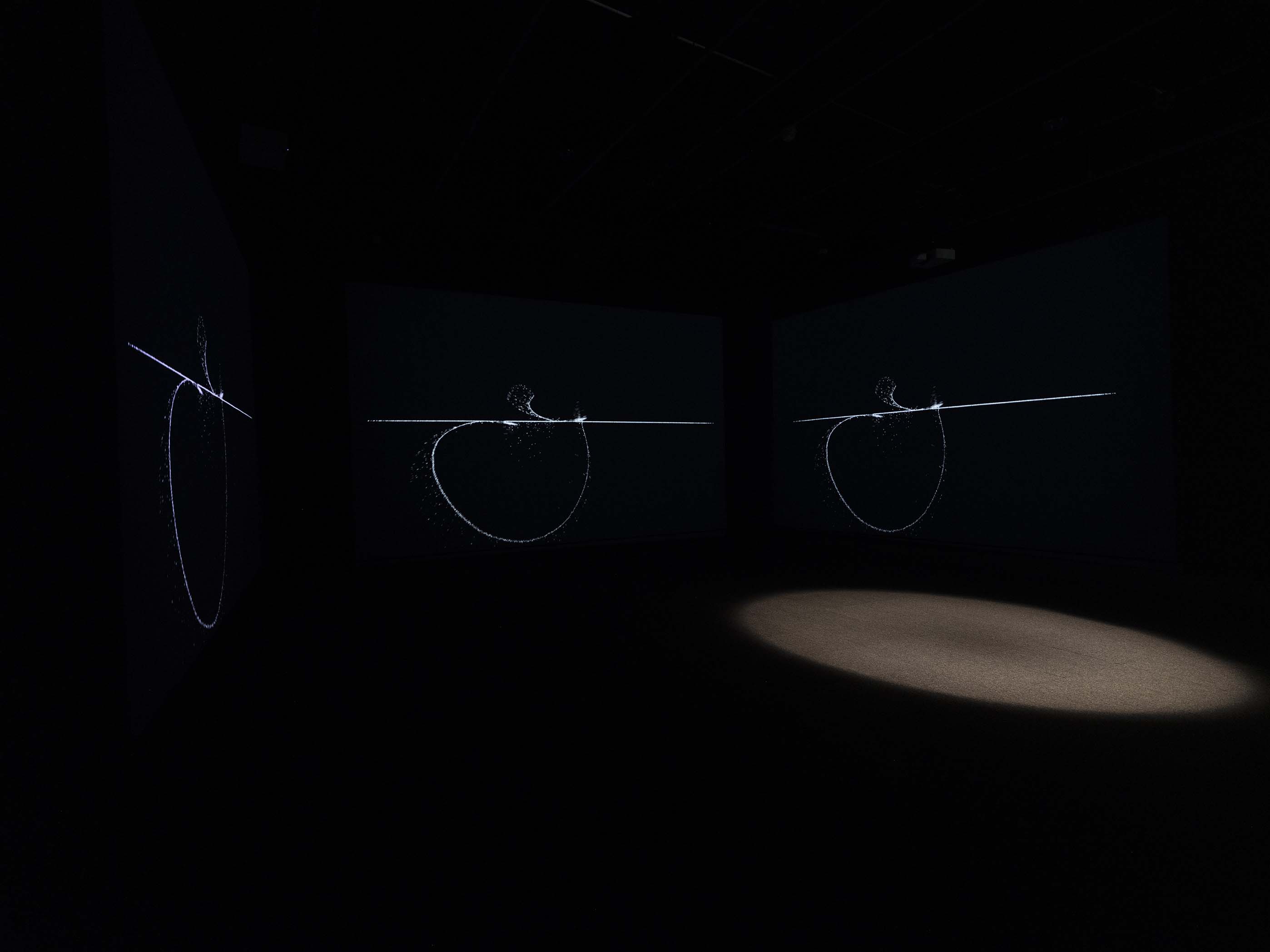

In Native (yugal/song), located in the second gallery space, the visitor encounters three video screens on three walls and becomes immersed in video images that have become abstractly visible via the soundtrack. r e a is interested in experimenting with the spatialisation of experience, and hopes that the historic photographic archives will come to life here as ghostly images start to appear on the screen. Of those who have been invisible, stolen, forgotten. For this sequence, r e a said they were revisiting imagery and sounds that “resonate through their ancestors and elders”, especially when they are on Country.12

r e a, Still image from Native 2024

r e a, Still image from Native 2024

Indigenous standpoint theory, new materialism, care/ empathy ethics and various readjustments of feminist critical theory and psychoanalysis have explored the ways in which feeling, emotion and sensation can radically change the world. This realm of experience has been reclaimed after decades of Western theory deemed it essentialist and part of the humanist concept of the individual self. Freud started it off by “discovering” the unconscious, but that too is likely, in all its interpretative performativity, to be a social construction after all. It has certainly been commodified by the Western canon.

The issue most pertinent now seems to be agency, and this requires that it be possible to act effectively from a multitude of points of difference.

North American scholar and anthropologist Faye Ginsburg has been following Indigenous digital and film/TV culture in Australia for years and has deemed it a “new wave” because she sees aspects in common with the radical French new wave cinema of the 1960s.13 But Marcia Langton started the conversation in 1993 with her famous little book Well I Heard It on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television and before her the anthropologist Eric Michaels analysed the critical and experimental approaches to film and TV in remote Australia. His paper “Bad Aboriginal Art” is still a major contribution to critical theory and influenced generations of scholars.14 Electronic and digital media provide new platforms for artists. Writing in 2019, r e a said: “I found in digital media a creative space of seemingly limitless experimental possibility; a space where colonial trajectories were not dictatorial.”15 These installations provide viewers with immersive experiences that allow them to get close to the issues by deep listening and careful looking.

Notes

2. r e a and Vicki Crowley, “Postcolonialism Considered: An Interview with Digital Artist R e a,” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 19, no. 3 (1998): 357.

3. r e a, correspondence with the author, 10 December 2023.

4. r e a, correspondence with the author, 10 December 2023. For an extensive discussion see r e a—Regina Merle Saunders, “‘Vaguely Familiar’: Haunted Identities, Contested Histories, Indigenous Futures,” PhD thesis, University of NSW, Sydney. 2019, especially Chapter 2, where r e a discusses methodology and rights of access, saying: “Being Aboriginal myself did not mean I had axiomatic rights to this site, or rights of access to Dharug country. If anything, my being Indigenous complicated the conditions of my access,” 59.

5. The Institute was founded in Parramatta in 1815 and re established in Blacktown in 1823. For a concise history see Heidi Norman, “Parramatta and Black Town Native Institutions,” The Dictionary of Sydney, https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/parramatta_and_black_town_native_institutions. parramatta_and_black_town_native_institutions.

6. See Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho Analysis, trans. Alan Sheridan (London: Penguin, 1979).

7. Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis.

8. Rudyard Kipling published his poem “The White Man’s Burden” in 1899, championing imperialism, empire and colonisation. The title of the poem became a phrase in colonial history. Cornel West provides a compelling contemporary analysis of colonisation and notes that: “By 1914, European maritime empires had dominion over more than half of the land and a third of the peoples in the world – almost 72 million square kilometres of territory and more than 560 million people under colonial rule”. See Cornel West, “The New Cultural Politics of Difference,” October 53 (Summer 1990): 102. For a visual arts perspective see Melissa Banta, Curtis M. Hinsley, et al., From Site to Sight: Anthropology, Photography and the Power of Imagery (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1986).

9. The Native Institute was first based in Parramatta and later re established in Blacktown; an area that had previously been known as Blacks Town. See Norman, “Parramatta and Black Town Native Institutions.”

10. Nakata is a champion of standpoint theory and indigenous research pedagogy. See especially Martin Nakata, “Anthropological Texts and Indigenous Standpoints,” Australian Aboriginal Studies 1998, no. 2 (Autumn 1998): 3–10.

11. r e a, “‘Vaguely Familiar’”, 65.

12. r e a, in correspondence with the author, 10 December 2023. 13. Faye Ginsburg, “Australia’s Indigenous New Wave: Future Imaginaries in Recent Aboriginal Feature Films,” Adriaan Gerbrands Lecture, 29 May 2012, Leiden, The Netherlands, published online, https://satellitedreaming.com/sources/australia-s-indigenous new-wave, and “The Indigenous Uncanny: Accounting for Ghosts in Recent Indigenous Australian Experimental Media,” Visual Anthropology Review 34, no. 1 (Spring 2018): 67–76.

14. See Langton, Well I Heard It on the Radio; Eric Michaels, “Bad Aboriginal Art,” Art & Text no. 28 (March–May 1988): 59–73.

15. r e a, “‘Vaguely Familiar’,” 32. Also see r e a, Jennifer L. Biddle and Lily Hibberd, “The Artificial as an Intelligent Indigenous/ Indigenizing System: The Experimental Art and Artifice of r e a,” Visual Anthropology Review 39, no. 2 (Fall 2023): 459–74, https:// doi.org/10.1111/var.12284

© 2025 professor ANNE MARSH | SITE BY jamie charles schulz